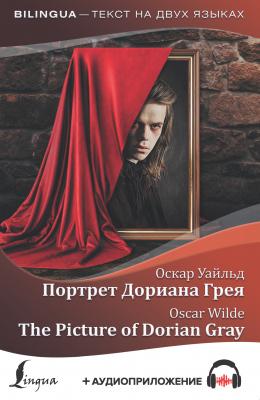

Портрет Дориана Грея / The Picture of Dorian Gray (+ аудиоприложение). Оскар Уайльд

Читать онлайн.| Название | Портрет Дориана Грея / The Picture of Dorian Gray (+ аудиоприложение) |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Оскар Уайльд |

| Жанр | Зарубежная классика |

| Серия | Bilingua (АСТ) |

| Издательство | Зарубежная классика |

| Год выпуска | 2020 |

| isbn | 978-5-17-118835-1 |

– Где это было? – спросил Холлуорд, несколько нахмурясь.

– Не смотри так сердито, Бэзил. Это было у моей тёти, леди Агаты. Она сказала мне, что обнаружила этого замечательного молодого человека. Он собирался помочь в её работе с бедняками лондонского Ист-Энда, и его звали Дориан Грей. Конечно, я не знал, что это твой друг.

– Очень рад, что ты этого не знал, Гарри.

– Почему?

– Я не хочу, чтобы вы встретились.

– Мистер Дориан Грей в студии, сэр, – сказал дворецкий, входя в сад.

– Ты должен теперь меня представить, – смеясь, воскликнул лорд Генри.

Художник повернулся к слуге.

– Попросите мистера Грея подождать, Паркер. Через минуту я приду.

Потом он посмотрел на лорда Генри.

– Дориан Грей – мой самый дорогой друг, – сказал он. – У него простая и прекрасная натура. Не порти его. Не пытайся на него повлиять. Твоё влияние было бы пагубным. Не отнимай у меня человека, который делает меня истинным художником. Помни, Гарри, я верю тебе.

– Какую ерунду ты говоришь! – сказал лорд Генри, улыбаясь и беря Холлуорда под руку, он почти силком привёл его в дом.

Chapter 2

As they entered they saw Dorian Gray. He was sitting at the piano, with his back to them, and he was turning the pages of some music by Schumann. “You must lend me these, Basil,” he cried. “I want to learn them. They are perfectly charming.”

“That entirely depends on how you sit today, Dorian.”

“Oh, I am bored with sitting, and I don’t want a portrait of myself,” answered the boy, turning quickly. When he caught sight of Lord Henry, his face went red for a moment. “I am sorry, Basil, I didn’t know that you had anyone with you.”

“This is Lord Henry Wotton, Dorian, an old Oxford friend of mine. I have just been telling him what a good sitter you were, and now you have spoiled everything.”

“You have not spoiled my pleasure in meeting you, Mr. Gray,” said Lord Henry, stepping forward and offering his hand. “My aunt has often spoken to me about you. You are one of her favourites, and, I am afraid, one of her victims also.”

“I am in Lady Agatha’s black books at present,” answered Dorian. “I promised to go to a club in Whitechapel with her last Tuesday, and I forgot all about it. I don’t know what she will say to me. I am far too frightened to call.”

Lord Henry looked at him. Yes, he was certainly wonderfully handsome, with his curved red lips, honest blue eyes and gold hair. “Oh, don’t worry about my aunt. You are one of her favourite people. And you are too charming to waste time working for poor people.”

Lord Henry sat down on the sofa and opened his cigarette box. The painter was busy mixing colours and getting his brushes ready. Suddenly, he looked at Lord Henry and said, “Harry, I want to finish this picture today. Would you think it very rude of me if I asked you to go away?”

Lord Henry smiled, and looked at Dorian Gray. “Shall I go, Mr. Gray?” he asked.

“Oh, please don’t, Lord Henry. I see that Basil is in one of his difficult moods, and I hate it when he is difficult. And I want you to tell me why I should not help the poor people.”

“That would be very boring, Mr. Gray. But I certainly will not run away if you do not want me to. You don’t really mind, Basil, do you? You have often told me that you liked your sitters to have some one to chat to.”

Hallward bit his lip. “If Dorian wishes it, of course you must stay.”

Lord Henry took up his hat and gloves. “No, I am afraid I must go. Good-bye, Mr. Gray. Come and see me some afternoon in Curzon Street. I am nearly always at home at five o’clock. Write to me when you are coming. I should be sorry to miss you.”

“Basil,” cried Dorian Gray, “if Lord Henry Wotton goes, I will go too. You never open your lips while you are painting, and it is horribly boring just standing here. Ask him to stay. I insist upon it.”

“All right, please stay, Harry. For Dorian and for me,” said Hallward, staring at his picture. “It is true that I never talk when I am working, and never listen either. It must be very boring for my sitters. Sit down again, Harry. And Dorian don’t move about too much, or listen to what Lord Henry says. He has a very bad influence over all his friends, with the single exception of myself.”

Dorian Gray stood while Hallward finished his portrait. He liked what he had seen of Lord Henry. He was so unlike Basil. And he had such a beautiful voice. After a few moments he said to him, “Have you really a very bad influence, Lord Henry? As bad as Basil says?”

“There is no such thing as a good influence, Mr. Gray. All influence is immoral.”

“Why?”

“Because to influence someone is to give them your soul. Each person must have his own personality.”

“Just turn your head a little more to the right, Dorian, like a good boy,” said the painter. He was not listening to the conversation and only knew that there was a new look on the boy’s face.

“And yet,” continued Lord Henry, in his low musical voice, “I believe that if one man lived his life fully and completely he could change the world. He would be a work of art greater than anything we have ever imagined. But the bravest man among us is afraid of himself. You, Mr. Gray, are very young but you have had passions that have made you afraid, dreams —”

“Stop!” cried Dorian Gray, “I don’t know what to say. There is some answer to you, but I cannot find it. Don’t speak. Let me think. Or, rather, let me try not to think.”

For nearly ten minutes he stood there with his lips open and his eyes strangely bright. The words that Basil’s friend had spoken had touched his soul. Yes, there had been things in his boyhood that he had not understood. He understood them now.

With