Confidential Concepts, Inc.

Все книги издательства Confidential Concepts, Inc.Constable

John Constable was the first English landscape painter to take no lessons from the Dutch. He is rather indebted to the landscapes of Rubens, but his real model was Gainsborough, whose landscapes, with great trees planted in well-balanced masses on land sloping upwards towards the frame, have a rhythm often found in Rubens. Constable’s originality does not lie in his choice of subjects, which frequently repeated themes beloved by Gainsborough. Nevertheless, Constable seems to belong to a new century; he ushered in a new era. The difference in his approach results both from technique and feeling. Excepting the French, Constable was the first landscape painter to consider as a primary and essential task the sketch made direct from nature at a single sitting; an idea which contains in essence the destinies of modern landscape, and perhaps of most modern painting. It is this momentary impression of all things which will be the soul of the future work. Working at leisure upon the large canvas, an artist’s aim is to enrich and complete the sketch while retaining its pristine freshness. These are the two processes to which Constable devoted himself, while discovering the exuberant abundance of life in the simplest of country places. He had the palette of a creative colourist and a technique of vivid hatchings heralding that of the French impressionists. He audaciously and frankly introduced green into painting, the green of lush meadows, the green of summer foliage, all the greens which, until then, painters had refused to see except through bluish, yellow, or more often brown spectacles. Of the great landscape painters who occupied so important a place in nineteenth-century art, Corot was probably the only one to escape the influence of Constable. All the others are more or less direct descendants of the master of East Bergholt.

Art of the Eternal

Since the first funerary statues were placed in the first sepulchres, the ideas of death and the afterlife have always held a prominent place at the heart of the art world. An unlimited source of inspiration where artists can search for the expression of the infinite, death remains the object of numerous rich illustrations, as various as they are mysterious. The ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, the forever sleeping statues on medieval tombs, and the Romantic and Symbolist movements of the 19th century are all evidence of the incessant interest that fuels the creation of artworks featuring themes of death and what lies beyond it. In this work, Victoria Charles analyses how, through the centuries, art has become the reflection of these interrogations linked to mankind’s fate and the hereafter.

Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) was a Russian painter credited as being among the first to truly venture into abstract art. He persisted in expressing his internal world of abstraction despite negative criticism from his peers. He veered away from painting that could be viewed as representational in order to express his emotions, leading to his unique use of colour and form. Although his works received heavy censure at the time, in later years they would become greatly influential.

Fragonard

A painter and printmaker of the Rococo movement, Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806) is recognised as one of France’s most prolific artists. His genius however almost went forgotten after the Revolution due to the expanding influence of neo-classicism and the loss of his bourgeoisie clientele. He studied under the great Boucher and painted over 550 works in various genres including landscapes and portraits illustrating the erotic, the domestic and an abundance of religious scenery. His smooth brushstrokes never faltered in depicting the charm and wit of 18th century France. Fragonard’s talent lies in bringing his creations to life in a refined and decadent manner with Goncourt describing him as “the poet of the Ars Amatoria of the age”.

Kandinsky

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) was a Russian painter credited as being among the first to truly venture into abstract art. He persisted in expressing his internal world of abstraction despite negative criticism from his peers. He veered away from painting that could be viewed as representational in order to express his emotions, leading to his unique use of colour and form. Although his works received heavy censure at the time, in later years they would become greatly influential.

The Pre-Raphaelites

In the Victorian era, England – swept along by the Industrial Revolution, the Pre-Raphaelite fold, William Morris, and the Arts and Crafts movement – aspired to return to traditional values. Wishing to resurrect the pure and noble forms of the Italian Renaissance, a group of painters including John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Edward Burne-Jones, favoured Realism and Biblical themes. This work, with its informed text and rich illustrations, enthusiastically describes this singular movement which provided the inspiration for Art Noveau and Symbolism.

Pascin

Today still considered a “Bad Boy”, Pascin was a brilliant artist who lived and worked in the shadow of contemporaries such as Picasso, Modigliani, and several others. A specialist of the feminine form, his canvasses are as tormented as his party lifestyle. The artist, considered scandalous for the erotic character of his works, exhibited in numerous Salons, notably in Berlin, Paris, and New York.

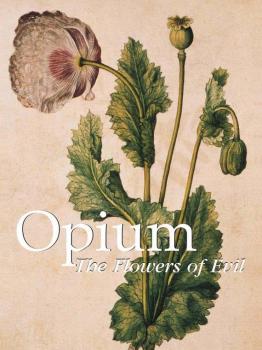

Opium. The Flowers of Evil

Opium, once used for ritual purposes, is a substance which dulls pain and offers access to an artificial world, and has long been idealized by artists and markets. Baudelaire, Picasso, and Dickens were all inspired to create by the blue clouds of smoke. Known as either a sacred drug or the worst of poisons, opium rapidly became popular in Great Britain and a source of commerce with Imperial China. This illustrated work presents the history and quasi-religious rites of opium’s use.

Art of India

If the ‘Palace of Love’, otherwise known as the Taj Mahal, is considered to be the emblem of Mughal Art, it is by no means the sole representative. Characterised by its elegance, splendor, and Persian and European influences, Mughal Art manifests itself equally well in architecture and painting as in decorative art.

Hokusai

Without a doubt, Katsushika Hokusai is the most famous Japanese artist since the middle of the nineteenth century whose art is known to the Western world. Reflecting the artistic expression of an isolated civilisation, the works of Hokusai – one of the first Japanese artists to emerge in Europe – greatly influenced the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters, such as Vincent van Gogh. Considered during his life as a living Ukiyo-e master, Hokusai fascinates us with the variety and the significance of his work, which spanned almost ninety years and is presented here in all its breadth and diversity.