Eugene Muntz

Список книг автора Eugene MuntzMichelangelo

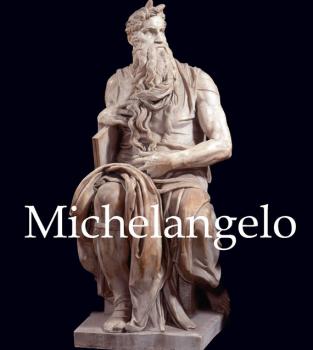

Michelangelo, like Leonardo, was a man of many talents; sculptor, architect, painter and poet, he made the apotheosis of muscular movement, which to him was the physical manifestation of passion. He moulded his draughtsmanship, bent it, twisted it, and stretched it to the extreme limits of possibility. There are not any landscapes in Michelangelo's painting. All the emotions, all the passions, all the thoughts of humanity were personified in his eyes in the naked bodies of men and women. He rarely conceived his human forms in attitudes of immobility or repose. Michelangelo became a painter so that he could express in a more malleable material what his titanesque soul felt, what his sculptor's imagination saw, but what sculpture refused him. Thus this admirable sculptor became the creator, at the Vatican, of the most lyrical and epic decoration ever seen: the Sistine Chapel. The profusion of his invention is spread over this vast area of over 900 square metres. There are 343 principal figures of prodigious variety of expression, many of colossal size, and in addition a great number of subsidiary ones introduced for decorative effect. The creator of this vast scheme was only thirty-four when he began his work. Michelangelo compels us to enlarge our conception of what is beautiful. To the Greeks it was physical perfection; but Michelangelo cared little for physical beauty, except in a few instances, such as his painting of Adam on the Sistine ceiling, and his sculptures of the Pietà. Though a master of anatomy and of the laws of composition, he dared to disregard both if it were necessary to express his concept: to exaggerate the muscles of his figures, and even put them in positions the human body could not naturally assume. In his later painting, The Last Judgment on the end wall of the Sistine, he poured out his soul like a torrent. Michelangelo was the first to make the human form express a variety of emotions. In his hands emotion became an instrument upon which he played, extracting themes and harmonies of infinite variety. His figures carry our imagination far beyond the personal meaning of the names attached to them.

Raphael

Raphael was the artist who most closely resembled Pheidias. The Greeks said that the latter invented nothing; rather, he carried every kind of art invented by his forerunners to such a pitch of perfection that he achieved pure and perfect harmony. Those words, “pure and perfect harmony,” express, in fact, better than any others what Raphael brought to Italian art. From Perugino, he gathered all the weak grace and gentility of the Umbrian School, he acquired strength and certainty in Florence, and he created a style based on the fusion of Leonardo's and Michelangelo's lessons under the light of his own noble spirit. His compositions on the traditional theme of the Virgin and Child seemed intensely novel to his contemporaries, and only their time-honoured glory prevents us now from perceiving their originality. He has an even more magnificent claim in the composition and realisation of those frescos with which, from 1509, he adorned the Stanze and the Loggia at the Vatican. The sublime, which Michelangelo attained by his ardour and passion, Raphael attained by the sovereign balance of intelligence and sensibility. One of his masterpieces, The School of Athens, was created by genius: the multiple detail, the portrait heads, the suppleness of gesture, the ease of composition, the life circulating everywhere within the light are his most admirable and identifiable traits.

Michelangelo

Michelangelo, like Leonardo, was a man of many talents; sculptor, architect, painter and poet, he made the apotheosis of muscular movement, which to him was the physical manifestation of passion. He moulded his draughtsmanship, bent it, twisted it, and stretched it to the extreme limits of possibility. There are not any landscapes in Michelangelo's painting. All the emotions, all the passions, all the thoughts of humanity were personified in his eyes in the naked bodies of men and women. He rarely conceived his human forms in attitudes of immobility or repose. Michelangelo became a painter so that he could express in a more malleable material what his titanesque soul felt, what his sculptor's imagination saw, but what sculpture refused him. Thus this admirable sculptor became the creator, at the Vatican, of the most lyrical and epic decoration ever seen: the Sistine Chapel. The profusion of his invention is spread over this vast area of over 900 square metres. There are 343 principal figures of prodigious variety of expression, many of colossal size, and in addition a great number of subsidiary ones introduced for decorative effect. The creator of this vast scheme was only thirty-four when he began his work. Michelangelo compels us to enlarge our conception of what is beautiful. To the Greeks it was physical perfection; but Michelangelo cared little for physical beauty, except in a few instances, such as his painting of Adam on the Sistine ceiling, and his sculptures of the Pietà. Though a master of anatomy and of the laws of composition, he dared to disregard both if it were necessary to express his concept: to exaggerate the muscles of his figures, and even put them in positions the human body could not naturally assume. In his later painting, The Last Judgment on the end wall of the Sistine, he poured out his soul like a torrent. Michelangelo was the first to make the human form express a variety of emotions. In his hands emotion became an instrument upon which he played, extracting themes and harmonies of infinite variety. His figures carry our imagination far beyond the personal meaning of the names attached to them.

Michelangelo

Michelangelo, like Leonardo, was a man of many talents; sculptor, architect, painter and poet, he made the apotheosis of muscular movement, which to him was the physical manifestation of passion. He moulded his draughtsmanship, bent it, twisted it, and stretched it to the extreme limits of possibility. There are not any landscapes in Michelangelo's painting. All the emotions, all the passions, all the thoughts of humanity were personified in his eyes in the naked bodies of men and women. He rarely conceived his human forms in attitudes of immobility or repose. Michelangelo became a painter so that he could express in a more malleable material what his titanesque soul felt, what his sculptor's imagination saw, but what sculpture refused him. Thus this admirable sculptor became the creator, at the Vatican, of the most lyrical and epic decoration ever seen: the Sistine Chapel. The profusion of his invention is spread over this vast area of over 900 square metres. There are 343 principal figures of prodigious variety of expression, many of colossal size, and in addition a great number of subsidiary ones introduced for decorative effect. The creator of this vast scheme was only thirty-four when he began his work. Michelangelo compels us to enlarge our conception of what is beautiful. To the Greeks it was physical perfection; but Michelangelo cared little for physical beauty, except in a few instances, such as his painting of Adam on the Sistine ceiling, and his sculptures of the Pietà. Though a master of anatomy and of the laws of composition, he dared to disregard both if it were necessary to express his concept: to exaggerate the muscles of his figures, and even put them in positions the human body could not naturally assume. In his later painting, The Last Judgment on the end wall of the Sistine, he poured out his soul like a torrent. Michelangelo was the first to make the human form express a variety of emotions. In his hands emotion became an instrument upon which he played, extracting themes and harmonies of infinite variety. His figures carry our imagination far beyond the personal meaning of the names attached to them.

Leonard de Vinci

Léonard de Vinci (Vinci, 1452 – Le Clos-Lucé, 1519)Léonard passa la première partie de sa vie à Florence, la seconde à Milan et ses trois dernières années en France. Le professeur de Léonard fut Verrocchio, d'abord orfèvre, puis peintre et sculpteur. En tant que peintre, Verrocchio était représentatif de la très scientifique école de dessin ; plus célèbre comme sculpteur, il créa la statue de Colleoni à Venise. Léonard de Vinci était un homme extrêmement attirant physiquement, doté de manières charmantes, d'agréable conversation et de grandes capacités intellectuelles. Il était très versé dans les sciences et les mathématiques, et possédait aussi un vrai talent de musicien. Sa maîtrise du dessin était extraordinaire, manifeste dans ses nombreux dessins, comme dans ses peintures relativement rares. L'adresse de ses mains était au service de la plus minutieuse observation, et de l'exploration analytique du caractère et de la structure de la forme. Léonard fut le premierdes grands hommes à désirer créer dans un tableau une sorte d'unité mystique issue de la fusion entre la matière et l'esprit.

Leonard de Vinci

Léonard de Vinci (Vinci, 1452 – Le Clos-Lucé, 1519)Léonard passa la première partie de sa vie à Florence, la seconde à Milan et ses trois dernières années en France. Le professeur de Léonard fut Verrocchio, d'abord orfèvre, puis peintre et sculpteur. En tant que peintre, Verrocchio était représentatif de la très scientifique école de dessin ; plus célèbre comme sculpteur, il créa la statue de Colleoni à Venise. Léonard de Vinci était un homme extrêmement attirant physiquement, doté de manières charmantes, d'agréable conversation et de grandes capacités intellectuelles. Il était très versé dans les sciences et les mathématiques, et possédait aussi un vrai talent de musicien. Sa maîtrise du dessin était extraordinaire, manifeste dans ses nombreux dessins, comme dans ses peintures relativement rares. L'adresse de ses mains était au service de la plus minutieuse observation, et de l'exploration analytique du caractère et de la structure de la forme. Léonard fut le premierdes grands hommes à désirer créer dans un tableau une sorte d'unité mystique issue de la fusion entre la matière et l'esprit.

Leonardo da Vinci

"War Leonardos deutliche Berufung zur wissenschaftlichen Forschung eine Hilfe oder ein Hindernis fur seine Arbeit als Kunstler? Er wird gewohnlich als ein Beispiel fur die Moglichkeit eines Bundnisses von Kunst und Wissenschaft angefuhrt. In ihm, so heit es zumeist, erhielt das schopferische Genie durch die analytische Fahigkeit zusatzlichen Antrieb; der Verstand verstarkte die Vorstellungskraft und die Gefuhle".

Leonardo da Vinci

"War Leonardos deutliche Berufung zur wissenschaftlichen Forschung eine Hilfe oder ein Hindernis fur seine Arbeit als Kunstler? Er wird gewohnlich als ein Beispiel fur die Moglichkeit eines Bundnisses von Kunst und Wissenschaft angefuhrt. In ihm, so heit es zumeist, erhielt das schopferische Genie durch die analytische Fahigkeit zusatzlichen Antrieb; der Verstand verstarkte die Vorstellungskraft und die Gefuhle".

Michelangelo

Miguel Ángel, al igual que Leonardo, fue un hombre de muchos talentos: escultor, arquitecto, pintor y poeta; logró expresar la apoteosis del movimiento muscular, que para él era la manifestación física de la pasión. Llevó el arte del dibujo a los límites extremos de sus posibilidades, estirándolo, moldeándolo y hasta retorciéndolo. En las pinturas de Miguel Ángel no hay paisajes de ningún tipo. Todas las emociones, todas las pasiones, todos los pensamientos de la humanidad están personificados, para él, en los cuerpos desnudos de hombres y mujeres. Rara vez concibió formas humanas en poses de inmovilidad o reposo. Miguel Ángel se convirtió en pintor para poder expresar en un medio más maleable lo que su alma de titán sentía, lo que su imaginación de escultor veía, pero que la escultura le negaba. Así, este admirable escultor se convirtió en el creador de la decoración más lírica y épica jamás contemplada: la Capilla Sixtina en el Vaticano. La vastedad de su ingenio está plasmada sobre esta vasta superficie de más de 900 metros cuadrados. Cuenta con 343 figuras principales con una prodigiosa variedad de expresiones, muchas de ellas en tamaño colosal, y además un gran número de personajes secundarios que se introdujeron como efecto decorativo. El creador de este gigantesco diseño tenía sólo treinta y cuatro años cuando comenzó su trabajo. Miguel Ángel nos obliga a ampliar nuestro concepto de lo que es la belleza. Para los griegos se trataba de la perfección física, pero a Miguel Ángel poco le importaba la belleza física, salvo en ciertas ocasiones, como en el caso de su pintura de Adán en la capilla Sixtina y de sus esculturas de la Pietà. Aunque era maestro en anatomía y en las leyes de la composición, se atrevió a hacer caso omiso de ambas cuando le era necesario para expresar sus ideas: exageraba los músculos en sus figuras y hasta las colocaba en posiciones que el cuerpo humano no puede asumir naturalmente. En una de sus últimas pintura, El juicio final en el muro del fondo de la Capilla Sixtina, dejó fluir su alma como en un torrente. Miguel Ángel fue el primero en hacer que la figura humana expresara una amplia variedad de emociones. En sus manos, la emoción se convertía en un instrumento que podía tocar para extraer temas y armonías de infinita diversidad. Sus figuras llevan nuestra imaginación mucho más allá del significado personal de los nombres que poseen.