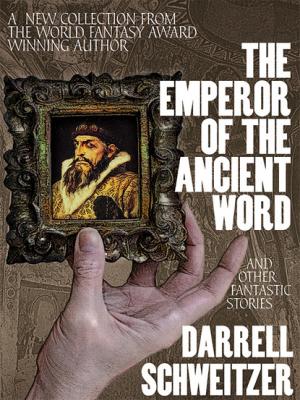

The Emperor of the Ancient Word and Other Fantastic Stories. Darrell Schweitzer

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Emperor of the Ancient Word and Other Fantastic Stories |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Darrell Schweitzer |

| Жанр | Историческая фантастика |

| Серия | |

| Издательство | Историческая фантастика |

| Год выпуска | 0 |

| isbn | 9781479409419 |

BORGO PRESS BOOKS BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER

Conan’s World and Robert E. Howard

Deadly Things: A Collection of Mysterious Tales

Echoes of the Goddess: Tales of Terror and Wonder from the End of Time

The Emperor of the Ancient Word and Other Fantastic Stories

Exploring Fantasy Worlds

The Fantastic Horizon: Essays and Reviews

Ghosts of Past and Future: Selected Poetry

The Robert E. Howard Reader

Speaking of Horror II

Speaking of the Fantastic III: Interviews with Science Fiction Writers

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2000, 2002, 2001, 2002, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2011, 2013 by Darrell Schweitzer

Cover art copyright © 2013 by Jason Van Hollander

Published by Wildside Press LLC

www.wildsidebooks.com

DEDICATION

For Mattie, Once Again

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

I’ve come to the conclusion that unless one can write them as engagingly as Harlan Ellison does, long introductions to collections of one’s own stories are usually not a good idea. Here are some of my best stories from the past ten years or so, which I hope you will enjoy. That’s really all I have to say. If you are going to enjoy them, you might as well get past the introduction quickly and begin.

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.

—Darrell Schweitzer

Philadelphia

March 2013

AT THE TOP OF THE BLACK STAIRS

It was a stirring of dust that roused King Vardabates back from the sleep of death. He was himself dust then, oblivious in the Land Beneath the World, but a voice seemed to blow upon the dust, like breath, and the voiced called out his name and bade him come forth, and he had neither strength nor will to resist. And so, as if a faint breeze had arisen on a hot, still summer’s day (although in the Land Below the World there are never any breezes), the dust arose into the air, less substantial than smoke, but assuming a shape of a sort.

And King Vardabates awoke from a featureless dream, into the dream of memory. He did not recall, at first, that he had ever worn a crown or commanded armies, or the splendor of his processions or the magnificence of his palace, which still stands in Bersion, beyond the Merimdean Sea.

No, his first memory was of a sunrise, glimpsed through the window when he was an infant, and then there was the feel of hot stones beneath his bare feet, when he ventured out into a courtyard in the hot sun, and was scolded by his nurse for being dirty.

Remembering that, he took a step forward, and felt nothing, and drifted life a cloud of dust on a wind that was impossible in the Land Below the World.

Still the voice called out to him, not in any language the king had spoken in life, but in the universal speech of the dead, “Arise, Vardabates, arise. I, Urcilak, summon thee.”

Now his passage over the flat, grey plains left a kind of track, not in the dust itself, but in the memories of ghosts, aroused by motion, the slow regathering of his mind, like a cloud that has been dispersed, coming together again. These others reached up, to touch him, insubstantial as he might be, that they might cling to something, and whisper their memories, that those memories might not be utterly forgotten: a song, a storm at sea, a night of love or rage, the terror of battle, the relief and joy of homecoming.

Now the eyes of Vardabates opened, and he gazed across the featureless, horizonless landscape, and up at the grey sky and the few pale stars, and he remembered another sky, far darker, where this was the color of thick smoke, and other stars, vivid and brilliant where these few were like failing embers.

By the time he reached the base of that vast, black tower, which reaches up out of the Land Beneath the World, into the World itself, he was able to touch the cold stone and feel it, to place his foot upon the first of the black stone steps within and rise to the second. Now all around him whispered a wind, descending the staircase from far above, the voices of the newly dead, pouring down out of the World, shouting out the last of their sorrows, their rage, the shock of departure from life, or even their grateful acceptance of same. In his ears, King Vardabates heard them, inasmuch as he had ears, and he heard among the babble of voices some speech he recognized, from his own country, which he had heard before.

And the voice called him again, saying, “Vardabates, King, come forth,” and he had the strength to push against the current of the wind within the tower, to rise up, up, and around, as the stairway spiraled. The name Urcilak remained with him, like a thorn in his flesh, tearing, but he could not place it, could not find its meaning or significance. The pain of it kept him going.

It was only as he reached the top of the black stairs, with the wind of descending spirits swirling around his ankles, that he knew who he was, that he remembered his crown, and there came to him another name, Andrathemne, whom he had loved.

Now he stood on the threshold before a low, vaulted room at the top of the tower, where two shrouded figures sat at table, playing a game on a board. He saw that both figures were hard and skeletal, that there was only dread in their features, and he knew that these two were Time and Death. Yet, because they were engrossed in their game, and had set aside the accoutrements of their offices—a scythe leaned against the wall, and an hourglass and a sack of seed rested on a window ledge—he did not know which figure was which.

Because he had been, because he was a king who had led armies, he boldly approached to observe their game.

On the board were figures carven of bone, like unto ships or castles or cities, or even in the shapes of individual men and women. One of the players held what might have been a king in his thin hand, in the midst of a long pause.

Now King Vardabates thought to simply slip past these two, occupied as they were, and escape out the door behind them as a truant child might; but he knew he was a king now, and kings have honor and should not be sneaks.

When he spoke up, groping for words in the tongue of living men, he felt as a child again, inarticulately explaining himself before two powerful masters who were not inclined to hear.

“I am...I have to get by. I’m summoned.... Someone knows my name.”

Now one of the figures turned toward him, its face pale and pitted, yet gleaming like a newly-risen moon. It leaned down and whispered into his ear.

“We know. Go, and take our message into the world of living men.” And the other whispered the message at some length, and now King Vardabates was much closer to being actually alive, for he was afraid.

Then he hurried from the room, out the door, and climbed up that long, dark slope down which the ghosts of the dead come streaming, before they reach the black tower. Indeed, now, it was as if he struggled against a torrent. Now the voices of the newly-dead shouted all around him, and their hands clutched at him, trying to drag him with him, outraged that he should be able to defy the order of things, and return where they could not.

As his feet found purchase in that hillside and he leaned into the wind, it seemed that he came together, bone unto his bone, and the dry earth became his flesh. Yet there was no breath in him, and he was not alive; yet animate, more substantial now, he made his way up, and clutched with his hands the edge of that stone wall which guards the borderlands of the afterworld.

At once an alarm was sounded, and borderers came racing to confront him, living men, weary priest-soldiers in tarnished armor, whose task it was to drive back such invaders as himself, that the dreams of men might be untroubled.

Yet