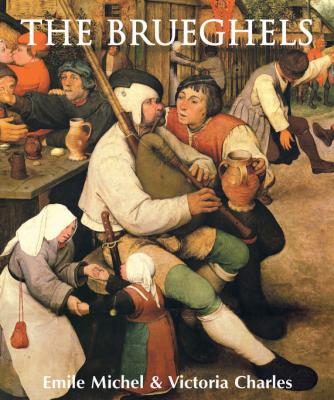

The Brueghels. Victoria Charles

Читать онлайн.| Название | The Brueghels |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Victoria Charles |

| Жанр | Иностранные языки |

| Серия | Temporis |

| Издательство | Иностранные языки |

| Год выпуска | 2016 |

| isbn | 978-1-78310-763-6, 978-1-78042-988-5 |

A few days later, a crowd of people from Ghent, including many women, walked all the way to the walls of Bruges, 32 kilometres away, just to attend a sermon. Every evening men and women walked through the streets singing Psalms arm in arm. In the marketplace, the people applauded jesters’ songs ridiculing the clergy with the refrain “Vive le gueux!” Caricatures and their accompanying texts began to appear, such as a church being shaken by three men while a group of – priests attempted to shore it up. Underneath the portrayal of the destruction the caption read, “The Lutherans in Germany, the Huguenots in France, and the gueux in Holland cast the Catholic Church to the ground”. From the mouths of the priests the author added, “If all three continue to shake, adieu Roman Church and its business”.

In Antwerp people sold pictures of a parrot in a cage. A monkey named Martin tried to rip it apart with its claws and teeth, and then a calf trampled the cage with such force that it was completely destroyed. The parrot was a symbol of the Catholics and the cage their power. The monkey, Martin, was none other than Luther himself, the man who had laid bare the deceit of the clergy; and the calf was a representation of Calvin, who was expected to completely annihilate the power of the church. The Catholics responded with their own caricatures (against the gueux) that called them good-for-nothings, vagabonds and pillagers. In turn, the Protestants called the priests jesters, acrobats and conjurers, saying that they juggled at the altar like conjurers practising sleight-of-hand.

16. Hans Holbein the Younger, Erasmus of Rotterdam, ca. 1523.

Tempera on linden panel, 36.8 × 30.5 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Between 11 and 17 August, the iconoclasts invaded Western Flanders. “They formed a band of three thousand Flemish and Walloons with a look of adventurers and louts. They were accompanied by twenty horsemen who seemed to be of noble birth. In bands of eighteen to twenty they invaded the churches, destroying painted and sculpted images and tearing to shreds the brocaded canopies, tunics and chasubles…”. These odious brutes were nevertheless honest. Van Vaernewyck attests that in certain towns, after having melted down, weighed and inventoried the ciboriums and sacred vases, these were surrendered to the authorities.

In Ghent, the iconoclasts called for the “removal of idols”. The bailiff, who sensed his relative powerlessness, procrastinated. Furious mobs sacked the churches and convents one after another, scandalously damaging the Abbey of Saint-Pieter. In vain, the abbot offered the mob a great deal of money to remove the art without destroying it, but to the cry of “Hop! Hop! It’s done!” the fanatics tore everything down.

“They even profaned the saints’ shrines. The wild mob opened the reliquaries and threw the relics and bones out the windows and into the wind, saying they looked like ordinary bones and that they had a terrible stench. The abbot and his monks kept quiet and did not dare to thwart the boors. It is said that one of the mob held a pistol to the abbot’s chest, asking if he planned on opposing what was being done to his convent. The abbot replied: ‘I shall do no such thing’. It is said that the monastery was pillaged for over 11,000 pounds worth of marble, alabaster, touchstone, and other precious materials, and that the wine cellars of the convent were sacked during the evening and the night of 22 August, for over 900 florins of wine. In certain parts of the cellar, beer and wine reached the tops of the men’s shoes”. During the night of the pillaging, the wine-soaked horde overran the town against the wishes of the very leaders of their movement, “such that no church, chapel, convent or hospice no matter how small or poor was safe from harm”.

The iconoclasts set to work in Antwerp on 20 August: “It was a Tuesday, around four in the afternoon. The devils started by mocking certain statues enclosed by the church of Notre-Dame. Addressing a statue of Mary they said, ‘Hello there Marietta of the carpenters,’ or even ‘Hello there icons, you’ll be struck down before long’. Then one of the leaders of the fools, a good-for-nothing, mounted the pulpit and began to preach, being pulled back down, he climbed up again and was driven out again, but those who forced him out were beaten with the butts of the muskets that some of the gueux wore hidden beneath their capes. A mob came running, and one of the richest churches in Europe was so brutally pillaged that nothing was left except shapeless rubble, even the metal parts of the chapels and altars”.

17. Quentin Metsys, Christ Presented to the People, ca. 1515.

Oil on panel, 160 × 120 cm.

Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Despite the fact that the violent movement lasted only a few weeks, it resulted in deep and lasting unrest. The authorities, whether they liked it or not, were forced to allow the practices of the dissident religions. In the towns, wooden churches were built, and in the country the new rites and offices were celebrated in barns. Brawls broke out between Catholics, Lutherans and Calvinists, between civilians and soldiers. These soldiers, groups of Walloons, German mercenaries (lansquenets), and Spanish infantrymen (fantassins), lived off the native population as though they had conquered a new land.

They made incursions into the countryside, where they emptied cellars and granaries of their provisions, took away fabric, clothes and furniture, and drove away the livestock. “They allege that they are poorly paid and that they must live in some manner. They promise to pay well those that lodge them; but they never keep their word. If they do pay at all, it is in cavalier’s currency (that is to say, in blows from the broadside of their sword)”. Three brothers, all slaughterhouse workers, picked a fight with a soldier and cut his throat like they might a beast’s. “The wounds were so large that one could place one’s hands inside them”. In a free-for-all that broke out between Walloon soldiers (“the red hoquetons”) and the bourgeois, a man named Jacques Hesscloos, who was the valet of a company of arquebusiers, seized an ash pole. “All of the Walloons that found themselves in his path were beaten down. He struck their arms with such terrible blows of his club that their rapiers flew in all directions and littered the ground around him. He struck their sides and shoulders so heavily that they fell to the ground with a single blow. Excited by the battle, he ripped the bands ornamenting the shoes of the Walloon soldiers, defying them to approach…”.

Van Vaernewyck recounts these bits of news by the hundred. Alarm bells rang out across the countryside, and peasants armed with pitchforks fell upon their marauders. The land was filled with shady characters, vagabonds and bandits. The act of begging, which had been encouraged by the large number of charitable institutions founded in the Middle Ages, increased to take on appalling proportions, and emigration added yet another form of decay. “All of the Low Countries complains of having been deprived of its rich and honest merchants who had once assured the comfort of a considerable number of the poor. In the good towns, there remained only futureless and penniless indigents who could hardly feed themselves. Although it was the height of summer, a general misery was perceptible in Ghent, and the poorhouses were called upon for demands beyond their resources. Evidence of poverty could be seen in the weekly second-hand markets. Where there were once many clothes, brass, and pewter objects for sale, now there was scarcely any, for the needy had sold everything, save the miserable clothes they wore. They were hopeless and without any other resources. They filled the streets, forced by desperation to pick through the