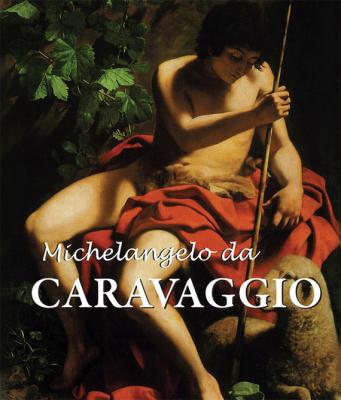

Michelangelo da Caravaggio. Félix Witting

Читать онлайн.| Название | Michelangelo da Caravaggio |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Félix Witting |

| Жанр | Иностранные языки |

| Серия | Best of |

| Издательство | Иностранные языки |

| Год выпуска | 2016 |

| isbn | 978-1-78310-027-9 |

From 1599 onwards, Caravaggio received his first commissions from the congregation of the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, for whom he painted The Calling of Saint Matthew, The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, and the famous Saint Matthew and the Angel. “Regarding the works created for the Cardinal del Monte in the Cantarelli chapel of the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Saint Matthew and the Angel could be found beneath the altar; on the right-hand side, the apostle is being called by the Redeemer and on the left he is being stabbed by his persecutor, with a crowd of onlookers.”[44] These works, which can still be found in part in that very chapel, are closely linked to the renown of the artist from Lombardy. Caravaggio’s teacher, Giuseppe Cesari, who had already decorated the ceiling of this chapel with frescos, is likely to have helped him to obtain this commission.[45] Caravaggio, who, it seems, never painted frescos, integrated his work into the completed decoration with monumental paintings set into the chapel. These canvases painted in oils did not really contribute to the budding Baroque style of the salons of the time, but the subtle technique and sombre colouring of their execution blended harmoniously with the light stucco of the space. The position of the chapel as the last on the left just before Rainaldi’s choir cupola, encouraged the painter to delve deeper into his imagination and resources. As the chapel was deliberately kept in darkness, the painter immediately set himself the task of introducing a scheme throughout the portrayals whereby the masses of light and shade and the coloured and neutral forms would be distributed between the works. In this way, only when all the works were seen together could their true effect be appreciated. A consideration for the architectonic conditions of the church building are clearly noticeable in the quieter composition of the left wall (The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew) and the scene of the right wall, which is built in a rising diagonal (The Calling of Saint Matthew), lending the chapel decorations as a whole an extremely organic integration into the building. The colouring is reduced to the strict minimum and the events are calculated in an almost authoritative manner, as is the setting of these events. On the whole, the light and colour are carefully shed on the elements that the painter chooses to stress. This realisation encouraged the artist to highlight the attributes of the figures as he had never done before, so that they almost became an artistic phenomenon.

Jakob Burckhardt explains that Caravaggio enjoyed proving to the observer that, despite all the holy events of former times, everything had happened in as ordinary a way as in the streets of end of the 16th century. He adds that Caravaggio loved nothing more than passion, whose volcanic eruption he could represent so well, even if he expressed it in numerous powerful, hideous characters.[46] This observation of the Romanesque element of the paintings positively highlight the way in which Caravaggio, and Baroque art as a whole, must have found essential. This counts as much for the representation of a being capable of arbitrary movement and its surroundings as for the use of purely sensual means, or even through the use of characteristic traits in the case of a portrait for example. It is on this that Caravaggio concentrates in his cycle of Saint Matthew in the Contarelli Chapel, much more so than in his bambocciate.[47]

Narcissus, 1598–1599.

Oil on canvas, 110 × 92 cm.

Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica di Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

The Taking of Christ, 1602.

Oil on canvas, 133.5 × 169.5 cm.

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

With this understanding of the intentions of the Roman Baroque artists, Caravaggio decided to use light to an even greater extent in his paintings, in order to highlight their demonic effect; this was the “light from above”,[48] which in reality resulted from the increasing use of lateral lighting in Baroque rooms, whether in churches, chapels or halls in the palazzi. With these natural architectural conditions, Caravaggio achieved a brilliant illumination in his paintings which, when positioned correctly, produced a wondrously harmonious effect.

The choice and application of the pigments went hand in hand with Caravaggio’s sense of artistic style. A distinct sulphur-yellow for the background and a luminous colour for the intermediary plane created the bearings from which he was able to form the space with his subject, and gave, from the first glance, a primary hierarchy to the scene. According to Baglione, however, this disorientated young artists, even the most talented amongst them. With these essential tools, Caravaggio created the foundations of a Baroque style which prevailed throughout the 17th century, and which was entirely different to the style of his pre-Roman works. Therefore, when Federigo Zucchero declared in front of Caravaggio’s paintings in San Luigi dei Francesi that he saw nothing in them but Giorgione’s thoughts,[49] then his judgement meant little more than an exhortation that Caravaggio should work towards an even more personalised manner of painting. At heart, the heroic character of the works had nothing in common with the balanced style of the Venetian master of the High Renaissance.

The chapel achieved its full effect through Caravaggio’s work of art, which at that time was on the altar. It depicts Saint Matthew and the Angel and is now in the art gallery of the Berliner Museum, in trust.[50] “The work pleased no one,” reported Baglione, so that it required the artistic sense of the Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani to save the rejected picture. “The latter took them, because they were the works of Caravaggio,” adds the biographer. If we look past the extremely realistic figure of the Evangelist, which at first does not stand out, and focus on the activity of the scene, the eye is drawn into a whirl of highs and lows, of heights and depths, of light and shade, and of coloured and monochrome areas, whose harmonious application and distribution suggest an eminently personal artistic sense. Palestrina’s style of mass setting would have to be called upon in order to characterise this peculiar overlapping of arioso and recitativo secco, and to describe the attraction of this most daring of Caravaggio’s compositions. The angel, who holds the hand of the bending Evangelist in a slightly affected manner, is very close in style to the shepherd boy from the Capitolinian Collection, and the Cupid of the two allegories of love. However, here, he appears even more natural and sovereign-like – a real model for Saraceni, who tried to capture this element of Caravaggio’s art, without, as the angel in his Rest on the Flight into Egypt in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj in Rome shows, achieving the rigorous strength of his teacher.[51] Caravaggio’s attempt to depict the messenger from heaven in a more adult, and at the same time more human, way than art had done so far cannot go unnoticed. In the same way that Cupid, traditionally represented as a putto, becomes an adolescent boy full of self-confidence and coquetry, Caravaggio’s depiction of the celestial companions of the holy figures is also radical.

His first successes, however, had a shadow cast over them by the refusal of several major works by some of his commissioners, as was the case in the cycle of Saint Matthew in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi. This was also the case in The Conversion of Saint Paul and The Crucifixion of Saint Peter destined for the Cerasi Chapel. Next, Caravaggio painted a Saint Anna Metterza, the Madonna dei Palafrenieri, which makes reference to the commissioners. Today, this painting can be found in the Borghese Gallery, and it is of the same style as that of the Madonna di Loreto, but further developed. The three figures, Saint Anne, the Virgin Mary, and the child Jesus, are depicted standing, almost like sculptures, an aspect which is all the more emphasised by the neutral background. The figure of the young Christ, who is portrayed as a boy of around ten years of age, symbolically crushes the head of a snake, and shows a close resemblance to the adolescent models of the altar-piece of San Luigi dei Francesi and the Madonna di Loreto. Mary appears more mature and detailed in comparison with the picture in San Agostino, while Saint Anna, as donna abbrunata, evokes the wailing old woman in The Entombment in the Vatican. The pale greenish tone that permeates the painting

Baglione, G.

Baglione, G.

Baglione, G.

Baglione, G.

Buckardt, J.

Witting, F. (1903).

Burckhardt, J.

Catalogue n° 365; canvas, height: 2.32 m × width: 1.83 m. Compare with Hirth-Murther, Cicerone der Königliche Gemäldegalerie Berlin (p. 111); Gesellschaft (Photographic Association), Berlin.

Catalogue n° 32; according to Eisenmann, (1879) and Burckhardt,