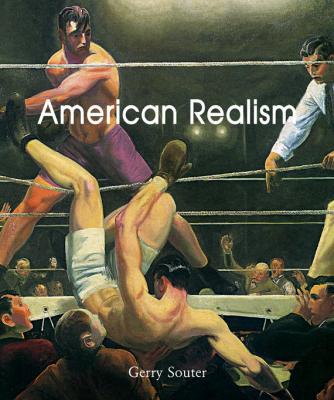

American Realism. Gerry Souter

Читать онлайн.| Название | American Realism |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Gerry Souter |

| Жанр | Иностранные языки |

| Серия | Temporis |

| Издательство | Иностранные языки |

| Год выпуска | 2016 |

| isbn | 978-1-78042-992-2, 978-1-78310-767-4 |

American Realism

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

Art © Estate of Thomas Hart Benton / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

© Charles Burchfield

© Everett Shinn

© John Sloan Estate, Artists Rights Society, New York, USA

Art © Estate of Grant Wood/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

American Gothic, 1930 by Grant Wood

© Andrew Wyeth

Introduction

Frederic Remington, Boat House at Ingleneuk, c. 1903–1907.

Oil on academy board, 30.5 × 45.7 cm.

Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, New York.

The concept of ‘Realism’ as applied to a style of art embraces too much with too little. You might as well try to define ‘Dance’ without looking at ballet, tap, jazz, clog or folk. It is true in art there is Cubism, Futurism, Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism and many more lesser ‘isms’ and each bears certain characteristics, or cleaves to certain constraints or expansions that define the style. Each of these styles has practitioners who themselves are defined by the results of their identification with the specific creative method. Each painter has also brought an individual contribution to the interpretation of the style. The key differences between these ‘isms’ and ‘Realism’ is time, place and state of mind.

A ‘Realist’ painter is the beneficiary of a legacy stretching back to the earliest cave paintings that describe the activities of our most primitive ancestors who ‘saw’ giant elk, mammoths, cave bears and their own humanoid brothers. They ‘saw’ the spears flying through the air, observed the graceful arch of the antelope’s neck and the hump of the buffalo’s back. They painted exactly what they saw, subjects standing still or in motion, in coloured clays mixed with animal fat and tallow. No one is sure if the result was pure journalism of observation or using magical suggestion to assure a successful hunt. The sophistication of interpretation wound its way through the centuries from the stylised propaganda scribed into the walls of tombs and temples to the sprawling epic of the Bayeux Tapestry documenting the Norman-french depredations on the shores of England. Religious faith was reinforced by depictions of stories from holy books such as the Bible, Qur’an, Bhagavad-Gita and the Analects of Confucius.

Realism has always dealt with the baggage carried by the interpreter of the scene. The practice of realistic painting produced an elitist class schooled in effects and techniques, and secret paint- and preservation-formulations, like alchemists granting eternal life to reality seen through their eyes and granting reality to scenes played out in their impassioned minds. Masters of technique became elevated in society and gathered together to protect their franchise with orders, academies and societies where membership was seen as a goal, an achievement, a sacred trust. To display their work or commission their skills bestowed a cachet, a symbol of piety, good taste and social responsibility.

Of course there were the malcontents: Dürer, Da Vinci, David, Rembrandt, Goya, Delacroix, Caravaggio; artists whose passion flowed from their brushes and etching needles and crayons to show there was more to realism than polished technique. When the American Colonies of the New World finally sought the trappings of civilisation after their Revolution and Westward Expansion, the Tripolitain War and the War of 1812 and the border wars with Mexico, both a native art and the arts of Europe began staking out new ground. All this civilisation arrived just in time for the birth of photography in the 1840s. The capturing of reflected light in an infinite scale of values preserved in silver halide crystals and fixed with hyposulphite forever democratised reality upside down and backwards on glass and paper, and held a mirror up to nature with the click of a mechanical shutter.

William Metcalf, Gloucester Harbour, 1895.

Oil on canvas, 66.4 × 74.3 cm.

Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts, gift of George D. Pratt.

And what did ‘true artists’ attempt to do with this brave new medium? Why, forced it to look like a painting, of course, and then hurried off to form orders, academies and societies and create rules of recognition for a ‘truly artistic’ photograph. The science and mechanics of photography originated in Europe, but its commercialisation, artistic pretension and ultimate creative potential were achieved in the United States, in the nation of immigrants who inherited the need to challenge the status quo. They passed along that need in their genes. The European wave of academic realism subsided at the hands of the nineteenth-century French Impressionists and tumbled into the larger-than-life theatricality and geographically diverse American scenes and lifestyles. Photography’s faithful translation of light and shadow into a reproducible image freed painters to pursue their imaginations. They could manipulate any of the elements: colour, line, perspective, placement, addition and subtraction, making the scene their reality. Realism as a monolithic, lock-step, strictly governed method of painterly visualisation shattered into nuances of interpretation.

Where you painted could make you a Regional Realist. What you painted might label you a Genre Realist, or who you painted classified your work as Portrait Realist – or maybe a Portrait Regionalist Realist if you painted Native Americans in the West, or sea captains on the East Coast. There were Realists who brushed the style of French Impressionism into every canvas and Academic Realists who dragged the dog-eared mechanics featured in Old World European salons into scenes of American life. Some Realists successfully stepped back and forth across the line between commercial illustration and fine art. Others took realistic subjects into the realms of surrealism or shaved the medium to such a fine point; the results of which challenged the photographic arts.

John Sloan, Gloucester Harbour, 1916.

Oil on canvas, 66 × 81.3 cm.

Syracuse University Art Collection, Syracuse, New York.

Of the variations cited, there are even further nuances that mock the concept of ‘American Realism’ as an all-embracing style. What remains are American Realist artists, each facing subject matter that is part of the fabric of the American scene. The result of their efforts is determined by the filtering of their perceptions through their individual intellects, skill sets, training, regional influences, ethnic influences and basic nurturing. If there is any binding together it is within the tradition of Realist Art in the United States, which accepts such a range from Winslow Homer’s poetic watercolours of the 1860s to the haunting minutiae of Andrew Wyeth and melancholy light of Edward Hopper in the 1950s and 1960s.

This book presents a cross-section of American Realist artists spanning more than one hundred years of art. It begins as some artists struggle with the influences of Europe, and other home-grown painters bring their nineteenth-century American scenes to life, and ends as today’s generation of Realist painters co-exist with American Modernism and absorb this new freedom into the latest incarnation of their art. The range of talent is exceptional, touching on the broadest interpretation of the American Realist artist. In examining this cross-section, we can better understand and appreciate the amazing diversity and the infinitely variable Realist styles.

Eastman Johnson (1824–1906)

Eastman Johnson, Woman in White Dress, c. 1875.

Oil on paper board, 56.8 × 35.6 cm.

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, San Francisco, California,