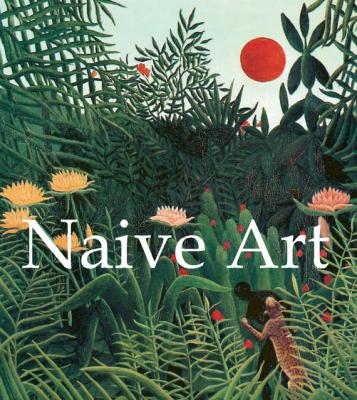

Naive Art. Nathalia Brodskaya

Читать онлайн.| Название | Naive Art |

|---|---|

| Автор произведения | Nathalia Brodskaya |

| Жанр | Иностранные языки |

| Серия | Mega Square |

| Издательство | Иностранные языки |

| Год выпуска | 2016 |

| isbn | 978-1-78160-825-8 |

“The essence of all genuine art is ultimately naïve if we understand this to mean purity of heart and thought.”

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© Estate Denis/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Vivin/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Larionov/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Matisse/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Gontcharova/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Chagall/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Kandinsky/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Bauchant/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Louis/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

© Estate Bombois/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

The Violin-Player, Mihail Dascalu

oil on canvas, 120 × 80 cm, Private collection

How Old is Naïve art?

There are two possible ways of defining when Naïve art originated. One is to assume that it happened when Naïve art was first accepted as an artistic mode of status equal to every other artistic mode. That would date its birth to the early years of the twentieth century.

The War of Independence

Traian Ciucurescu, 1877

Oil on glass, 30 × 25 cm

Private collection

The other is to apprehend Naïve art as no more or less than that, and to look back into human prehistory and to a time when all art was of a type that might now be considered Naïve – tens of thousands of years ago, when the first rock drawings were etched and when the first cave-pictures of bears and other animals were scratched out.

The War of Independence

Emil Pavelescu, 1877

Oil on canvas, 55 × 80 cm

Private collection

If we accept this second definition, we are inevitably confronted with the very intriguing question, ‘So who was that first Naïve artist?’ Many thousands of years ago, then, in the dawn of human awareness, there lived a hunter. One day it came to him to scratch on a smooth rock surface the contours of a deer or a goat in the act of running away.

Weaver Seen from Front

Vincent van Gogh, 1884

Oil on canvas, 70 × 85 cm

Rijskmuseum, Amsterdam

A single, economical line was enough to render the exquisite form of the graceful creature and the agile swiftness of its flight. The hunter’s experience was not that of an artist, simply that of a hunter who had observed his ‘model’ all his life. It is impossible at this distance in time to know why he made his drawing.

The Schuffenecker Family

Paul Gauguin, 1889

Oil on canvas, 73 × 92 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Perhaps it was an attempt to say something important to his family group; perhaps it was meant as a divine symbol, a charm intended to bring success in the hunt. From the point of view of an art historian, such an artistic form of expression testifies to an awakening of individual creative energy and a need, after its accumulation through the process of encounters with nature, to find an outlet for it.

Me, Landscape Portrait

Henri Rousseau, 1890

Oil on canvas, 143 × 110 cm

Narodni Gallery, Prague

This first-ever artist really did exist. He must have existed. And he must therefore have been truly ‘naïve’ in what he depicted because he was living at a time when no system of pictorial representation had been invented. Only thereafter did such a system gradually begin to take shape and develop. And only when such a system is in place can there be anything like a ‘professional’ artist.

Sign for a Wineshop

Niko Pirosmani

Oil on tin plate, 57 × 140 cm

Georgian Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi

It is very unlikely, for example, that the paintings on the walls of the Altamira or Lascaux caves were creations of unskilled artists. The precision in depiction of the characteristic features of bison, especially their massive agility, the use of chiaroscuro, the overall beauty of the paintings with their subtleties of colorations – all these surely reveal the brilliant craftsmanship of the professional artist.

A Woman’s Portrait

Henri Rousseau, 1895

Oil on canvas, 160 × 105 cm

Musée du Louvre, Paris

So what about the ‘naïve’ artist, that hunter who did not become professional? He probably carried on with his pictorial experimentation, using whatever materials came to hand; the people around him did not perceive him as an artist, and his efforts were pretty much ignored.

Faces in a Spring Landscape (The Sacred Wood)

Maurice Denis, 1897

Oil on canvas, 94 × 120 cm

Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Any set system of pictorial representation – indeed, any systematic art mode – automatically becomes a standard against which to judge those who through inability or recalcitrance do not adhere to it. The nations of Europe have carefully preserved as many masterpieces of classical antiquity as they have been able to, and have scrupulously also consigned to history the names of the classical artists, architects, sculptors and designers.

The Girl with a Glass of Beer

Niko Pirosmani

Oil on canvas, 114 × 90 cm

Georgian Museum of Fine Arts, Tbilisi

What chance was there, then, for some lesser mortal of the Athens of the fifth century BC who tried to paint a picture, that he might still be remembered today when most of the ancient frescoes have not survived and time has not preserved for us the easel-paintings of those legendary masters whose names have been immortalized through the written word?